Hello all.

As we drawn near to the spooky season, the scent of pumpkin spice lattes hangs in the air, sales of Count Chocula cereal begin to trend upward, all the streaming services start advertising their horror collections, and a not-so-young psychology professor’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of monsters.

(We’re going to pretend that I don’t think about monsters the rest of the year as well.)

This post is the first in a three-part series in which I turn my academic eye toward the subject of horror fiction. Today, I will focus on the question: what is horror? In the next post, I will ask why we like horror (a surprisingly complicated psychological question). And then I will wrap up my own personal Trilogy of Terror by seeing if this blood-drenched genre attracts a particular type of personality. A good time will be had by all who survive.

1: Emotion Research

One common topic among psychologists who study emotions is the question of whether or not there exists a set of basic emotions. Think of it like this: in chemistry, we have the periodic table of the elements. These elements are the basic building blocks, and when we combine them in different ways we get a wide range of possible molecules with different properties. Are there “elemental” emotions, with our many complex experiences being variations and combinations of these basic emotions?

One of the most famous researchers in this area is Paul Ekman, who began by looking at universal facial expressions, and developed an initial list of 6 basic emotions: happiness, sadness, fear, disgust, anger, and surprise. If that list looks familiar to you, there is a good reason for that. Paul Ekman was a scientific consultant for the Pixar film Inside Out, and the main emotional characters in that film are five of Ekman’s six (I can understand why they left surprise out. Imagine trying to write a character whose primary job is to be startled and say “what was that?”).

We can then look at complex emotional responses as combinations of these six. If I walk into a room, and my family jumps out from behind the furniture and shouts “happy birthday,” my feelings are a mix of surprise and happiness. If I walk into a room, and see that there is a rattlesnake next to my foot, it will be a mix of surprise and fear.

2: Horror As A Compound Emotion

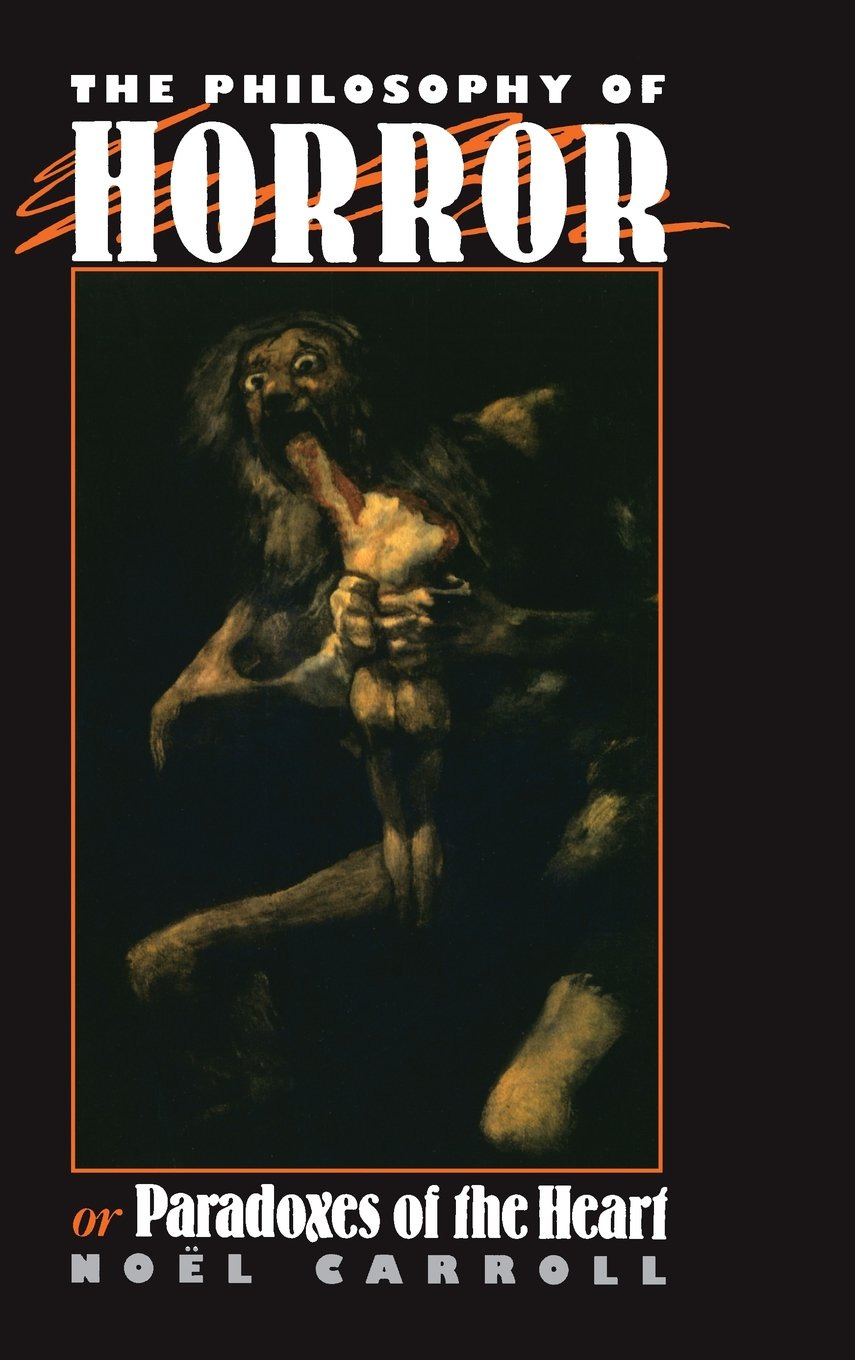

The philosopher Noël Carroll’s book The Philosophy of Horror, is a must-read if one wants to get into the scholarly study of horror. In this book, Carroll looks at this genre of fiction from several different angles, and I have found his theory to be useful in thinking about horror.

Carroll calls the emotion that he is studying the “art horror” response, referring to the audience’s horrified reaction to what is being presented on the page, or on the screen (or in your ear, if you like horror podcasts). It is important to distinguish between horror in response to art, and horror in response to real-world events. The psychology of how we respond to a good campfire story about an escaped lunatic with a hook for a hand is very different from the psychology of how we would respond if physically attacked by an actual murderer.

In art horror, the audience’s response is sympathetic, typically reacting to the emotions of the characters (or narrator). If a vampire walks into the room, and people start screaming and begging for a quick death, I am probably watching a horror movie. If a vampire walks into the room, and people wave and say “What’s up, Drac? Drink any good blood lately?” I’m probably watching the latest Hotel Transylvania movie or something like that, a comedy instead of horror.

Carroll argues that horror is a compound emotion, combining fear and disgust. Fear as an emotion functions to alert us to threats, and motivate us to escape them by flight or by fight. Disgust alerts us to possible contamination, and motivates us to avoid contact with the disgusting object. Horror requires both. Fear by itself shows us a threat, but many forms of fiction show us threats without being horror. An adventure film, for example, might feature terrorists threatening to detonate an atomic bomb in a densely-populated area. That’s a fearsome threat, but adventure movies are not horror movies. Disgust also is not enough. A story about someone who stepped in dog poop might elicit disgust, but not horror.

Literature and Film Studies Professor Bruce Kawin parallels Carroll, calling horror “a compound of terror and revulsion.” Horrific monsters are both threatening and nauseating in some way. To provide examples, I will look to two classic sources, and one contemporary. In Bram Stoker’s Dracula (the original book), when Jonathan Harker meets Count Dracula, he shakes the Count’s hand and describes it as being “more like the hand of a dead than a living man,” and talks about the “horrible feeling of nausea” that comes from being touched by the Count. The breath of Dracula is also described as nausea-inducing, and Mina talks about the “reeking lips” pressed to her throat when Dracula bites her.

H.P. Lovecraft is well-known for his cosmic horror stories, often emphasizing humanity’s terrible irrelevance in the face of incomprehensible elder beings. But when we get physical descriptions of monsters, Lovecraft gives us great examples of how fear and disgust combine. In “The Outsider,” Lovecraft talks about an undead creature crashing a party. As the guests flee in terrible fear, the narrator catches a glimpse of the thing: “I can not even hint what it was like, for it was a compound of all that is unclean, uncanny, unwelcome, abnormal, and detestable. It was the putrid shade of decay, antiquity, and desolation; the putrid, dripping eidolon of unwholesome revelation, the awful baring of that which the merciful earth should always hide.” You’ve got to love a good putrid and dripping undead creature.

I could multiply examples, but for a more recent example, to show the continued reliance upon disgust combined with fear in horror, I present Declan Finn’s Saint Tommy, NYPD series (urban horror combined with police detective stories). In the first book in the series, the main character has to deal with demonically-empowered killers whose strength and durability pose a genuine physical threat. But the most notable thing about these demonized characters, and what makes these horror novels, in addition to police procedurals, is that the main character can literally smell the evil in them: “It was so repulsive that when it hit me, I gagged, and nearly vomited. It was horrific, and ungodly, and those were the adjectives I used before I knew the source. If you’ve ever found a rotted human corpse, perhaps one dredged up from a body of water, you have some idea of what the stench was like. Then add in rotten eggs, fecal matter, sit and stew on a hot summer day for six hours.”

3. Carroll’s Theory of Monsters

Part of the revulsion cased by monsters in horror is not just that they might be slimy or decomposing, but that they strike us as deeply wrong. They defy our attempts to make sense of them. In one of his classic works on the topic, Lovecraft describes the dread created: “that most terrible conception of the human brain—a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.”

Carroll develops what he calls his “category-jamming” theory, a cognitive approach that focuses on our tendency to think in terms of mental categories.

Category-based thinking is one of the basic principles of how humans think. We assign objects to categories, and respond to them based on those categories. As I write this, I am drinking coffee. I know what coffee is and what I should do with it because I have a mental category of coffee. We use the stimulus features of an object that we encounter to place it in its proper category and understand it. This morning, before I began writing this, I dropped one of my kids off for a babysitting job. What greeted me at the door was a pair of small creatures. They had fur, four feet, floppy ears, wagging tails, and they barked at us. Because of those features, I knew that they were dogs (Basset Hounds, to be specific), and I knew how to react, because I love dogs.

Monsters strike us as wrong because they are category transgressors. A barking creature with a wagging tail, fur, floppy ears, and four feet is a dog. A barking creature with a wagging tail, fur, floppy ears, and a hundred feet is not a dog; it is some kind of monstrous dogipede that does not belong on God’s green Earth. It is, to use again Lovecraft’s words, a violation of “those fixed laws of Nature.”

The monster might violate categories by belonging to two or more incompatible categories. A zombie is living and dead. It is obviously a dead thing, but dead things do not walk around and eat brains. Only living things can do that. The human brain jams up at the sight of the walking dead. Cyborgs are human and machine. Werewolves are human and animal.

Along those lines, in my own fiction, the main character is attacked by an assassin that is a combination of human and a Central African hairy frog, and the main character also thwarts the evil plans of a collection of hyena-people.

The monster might instead be missing key features that are necessary for the category. The Headless Horseman is missing a head. People need heads if they are going to ride horses and chase Ichabod Crane. Ghosts are not only both dead and sort of acting like living things, but they are also missing their bodies.

Instead of missing features, there might be extra or exaggerated features. In addition to their other terrible characteristics, the xenomorphs in the Aliens films have two mouths. In the 2017/2019 It films, the shapeshifting evil clown Pennywise frequently has far too many teeth. A spider might be scary, but a fifty-foot tall spider is the basis for a solid creature-feature. One of the iconic images in the first Nightmare on Elm Street is Freddy extending his arms unnaturally long.

Finally, monsters might jam our categories by being literally incomprehensible, not fitting into any categories at all. The king of this is H.P. Lovecraft, of course. The cornerstone of Lovecraft’s horror is the inability to make sense of what the main character is witnessing, and many of his monsters defy all mental categories: “It was everywhere—a gelatin—a slime—yet it had shapes, a thousand shapes of horror beyond all memory. There were eyes—and a blemish. It was the pit—the maelstrom—the ultimate abomination. Carter, it was the unnamable!” (That, naturally, is from Lovecraft’s story “The Unnamable”).

Reflecting on Carroll’s category-jamming theory, I found myself at a loss when it came to a specific type of horror story; the slasher. With the exception of supernatural slashers such as Jason Voorhees or Freddy Kreuger (or both), the majority of “monsters” in slasher films are plain old humans, yet slasher films are commonly understood to be horror. Is that wrong? Should we reclassify slasher films without supernatural antagonists as crime thrillers or something like that? Is this a hole in Carroll’s theory? Berys Gaut criticizes Carroll on this point, saying that horror can come from slashers even though slasher antagonists are not category transgressors. Tamborini and Weaver, in their chapter on the history of horror, argue that the psychological pathology that drives slasher killers is “unexplainable” by audiences’ understanding of the human mind, making them sufficiently incomprehensible to be a violation of Nature without recourse to any considerations of category-jamming.

I think I might have it figured out, though. If monsters are “wrong” because they violate categories, slasher antagonists could still fit. One way that monsters violate categories is by lacking something essential to that category. When psychologists and philosophers talk about human nature, and ask what it is that makes humans unique, we most often get a two-part answer. Humans are rational animals; our cognitive capacities far outstrip those of any other animal species. Humans also are social animals; while there are social species such as wolves or bees, those groupings tend to be family-based. Humans create societies, with a level of organization and cooperation between genetically-unrelated members that is far beyond anything seen in the animal kingdom. The killer in a slasher film is most likely going to lack both of those features. They are often insane, lacking properly-functioning rational natures. And slasher antagonists are not known for their high levels of social functioning, inflicting suffering and death on the other humans instead of cooperating with them. By both of these standards, these killers are inhuman, and films like Silence of the Lambs and Seven could legitimately be classified as horror (I might take some flack from film nerds about this claim. Bring it on, Clarice).

What do you think? Are Carroll’s theories convincing? Am I completely off base when it comes to slashers? The comment section is below, so hit me with your analyses.

Next time, we will get into questions of emotion and motivation. Fear and disgust both work to motivate us away from the object in question. So why are so many of us drawn toward horror? I found a surprising number of fascinating theories, and in my next post I will throw them all into a terror-pit and see what explanations survive the carnage.

See you all then!