Hello all.

Welcome back for our latest installment in Psychology for Writers, a series in which I (a psychology professor and newbie fiction author) present information about topics in psychology that might be relevant to writers in a way that hopefully you will find helpful. Today, I want to talk about a particular approach to moral character, and how it can help us develop our (fictional) characters.

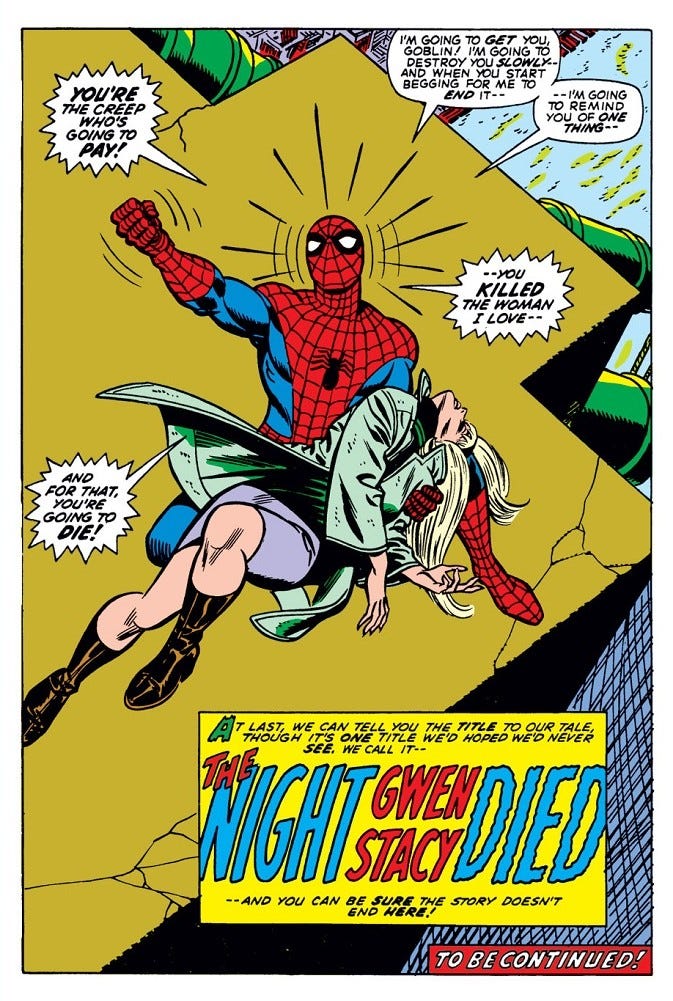

Spoiler Warning: I will be discussing the ultimate fates of some characters from various media. Fortunately, most of my examples are at least twenty years old, so the damage will be minimal if you proceed.

I am drawing here primarily from the work of Blaine Fowers, a psychology professor at the University of Miami, whose scholarship has had a substantial impact on my own approach to psychology. Fowers is originally a marriage counselor, but has since dedicated a considerable amount of time and effort to interdisciplinary work involving psychology and philosophy. Fowers is an Aristotelian psychologist, strongly influenced (as was I) by Alasdair MacIntyre, and the author of such books as The Science of Virtue, Virtue and Psychology, and a personal favorite of mine (if for no other reason than the amazing title) Beyond the Myth of Marital Happiness.

Here is a crash course on the relevant basics of the Aristotelian approach: In order to understand anything, we need to look at it in terms of its telos, the goal or purpose of the thing. The telos of a clock is telling time. The telos of a school is education. Situations also have a telos; if I am in a job interview, the goal being pursed is a job offer, so I should make decisions that move me toward that telos. Knowing the telos of a situation will guide my choices and help me know the right thing to do.

Mistakes and honest disagreements about the telos can give us tragic conflict between otherwise-heroic characters. In the (much-criticized for bad writing) Civil War story arc in Marvel Comics, the plan was for heroes to be drawn into one of two sides of the issue of government control of superhumans. What is the higher good to be pursued; freedom or security? As many people have noted, Inspector Javert in Les Miserables is not a villain, even if he is Valean’s enemy. Javert is motivated by a strong sense of justice, and sees his tracking of Valjean as the heroic pursuit of an escaped criminal who belongs behind bars. He is wrong, but not evil. If you haven’t heard it yet, do yourself a favor and listen to Norm Lewis’ take on Javert’s song “Stars.”

Fowers argues that we can also think about a person’s moral character in terms of their ability to size up a situation, know the correct goal, and pursue it. He lays out five character types, and it is worth our time to pay attention to this typology and consider what it means for our writing.

Virtuous

The first type is what Fowers calls the Virtuous character. This person consistently knows the telos to be pursued in any situation, and how to go about pursuing it. He knows the good, loves the good, and experiences no inner conflict about what to do. I have never met such a person in real life, and Fowers holds this type out only as an ideal that we might occasionally experience in our lives. In fiction, the Virtuous character has no inner turmoil about what to do; conflict in the story comes from the obstacles that need to be overcome and the villains that need to be defeated. Characters like this are also rare in contemporary fiction, since they tend to be looked on as simplistic and psychologically boring. The closest I can think of for this type of character is the square-jawed hero of the Saturday morning cartoons of my childhood, and of certain Silver-Age comics: flawlessly moral and always motivated by the highest good.

Continent

A more common heroic moral type is the Continent character. This person has a pretty good (though not always flawless) grasp of the right thing to do, but that knowledge clashes with desire. There is inner conflict between what the person knows is right and what the person wants. A good example of this is the classic heroic battle between justice and revenge, in which the character wants to do unrestrained violence in response to an evil act, but reins himself in and (begrudgingly) settles for defeating the villain.

In this scene from the movie Kindergarten Cop, the main character’s wrath is ignited by an abusive father, and his desire is to pound the man into a pulp. He pauses, understanding that this is not the right way to handle the situation, and his inner conflict is resolved in favor of allowing the justice system to handle the abuser. In one of the most well-known scenes in Doctor Who, the time-travelling Fourth Doctor has the opportunity to eliminate the murderous Daleks in an act that could be described as a pre-emptive genocide. But does he have the right? The Doctor desires to do the right thing, but is uncertain what the right thing is.

Incontinent

The next type in Fowers’ theory is the Incontinent. This type is similar to the Continent, because both struggle with inner conflict, knowing what they should do but not wanting to do it. The difference between the two is that the Continent person wins most of those inner battles, while the Incontinent most often loses them.

In a humorous example of this type, in the Looney Tunes short Birds Anonymous, Sylvester the Cat tries to give up his carnivorous pursuit of Tweety by going “cold turkey” and adopting a bird-free diet. In the climax, Sylvester breaks down weeping: “I gotta have a bird! I’m weak! I’m weak but I don’t care!” He knows what he should do, and desires to do it, but cannot make himself do it.

Incontinent characters can be sympathetic, with audiences seeing them as tragic figures who struggle but fail. In the TV series Heroes, Isaac Mendez (a superhuman who can paint the future, but only when high on heroin) might have eventually learned to access his powers while sober (two other characters show that this is possible), but in the end he returns to the needle. In The Sopranos, Tony wants to become a better man, but cannot escape his inner darkness or the allure of vice. The Canadian vampire-cop series Forever Knight has one of the biggest downer endings ever: after fighting for three seasons to overcome his vampiric nature and regain his humanity, Nick utterly fails, resulting in murder, despair, and suicide. Incontinent antagonists may not see themselves as villains, or may not want to be villains, but their vices overpower their virtues; their greed, or lust, or anger are calling the shots. Hans Gruber in Die Hard just wants money. Professor Callaghan in Big Hero 6 is blinded by his desire for revenge.

Beastly

While the Incontinent struggle against their vices and lose, the Beastly character is so far gone that there isn’t even a struggle anymore. This person has become so degraded that he or she has lost the human ability to reason, make choices, and relate to others. These characters serve only their animal appetites. In the film version of IT, Beverly’s father is a vile, abusive slime of a man, with no redeeming qualities, and no apparent inner conflict about what he does to her. Frank Cotton, in Clive Barker’s novella The Hellbound Heart (the basis for the first Hellraiser film), is thoroughly driven by his hedonism. In the same way that even the best of us might only become Virtuous on special occasions, characters of low moral quality do not need to remain so. In the comic book Daredevil: Born Again, Karen Page becomes Beastly when she hits rock bottom, so enslaved to drugs that she willingly betrays Daredevil for a hit, sparking the beginning of her redemption arc.

Vicious

The last type in Fowers’ theory gives us (in my opinion) the most interesting kind of antagonist. What Fowers calls the Vicious type has many of the virtues that empower excellence, but is mistaken as to the telos. They believe that they are doing good, but they are not aligned with true goodness. These characters generally think that they are the heroes, and are like the Virtuous character in that we rarely see inner conflict over their actions. When written well (the quality of writers we are given in the world of comic books varies widely), Doctor Doom is courageous, brilliant, self-controlled, and insightful. He attempts to conquer the world because he genuinely believes that he could make Earth a paradise if he ruled it. His error is in believing that the good life for humans is found in a “benevolent” tyranny. A similar error is made by Grand Admiral Thrawn in Timothy Zahn’s original trilogy of Star Wars novels; Thrawn believes that the Empire is the best way to establish a good galactic society. Alfred Bester, the ruthless telepath in Babylon 5, sees himself as the guardian of a persecuted minority (telepaths). Bester’s error is his belief that establishing telepaths as a ruling class is the proper telos to be pursued.

Fowers’ theory gives us a way to organize some of our thoughts about characters. When we make morally-praiseworthy decisions and act on them, it is because we (1) know the good (2) desire the good, and (3) are able to pursue the good. How well do your characters perform at these three things? How is conflict between characters shaped by incompatible beliefs and desires about the good, or their relative abilities to act in accordance with their knowledge and desire?

I hope that you found this helpful. If you did, don’t forget to hit that Subscribe button so you won’t miss out on other installments. And if you have thoughts, questions, or disagreements, let me know in the comments section below. See you all next time!