Hello all.

Welcome back for our latest installment in Psychology for Writers, a series in which I (a psychology professor and newbie fiction author) present information about topics in psychology that might be relevant to writers in a way that hopefully you will find helpful. Today, we will be doing a bit of mythbusting, focusing on one of psychology’s urban legends.

We all try to avoid as much inaccuracy in our writing as possible. Everybody makes mistakes, and most readers are content to let minor details slide, but glaring falsehoods just make writers look stupid, and make people laugh at us instead of enjoying our stories. If I write a samurai drama, but set it in the 5th Century BC, I look like an ignoramus. If I describe a character’s pistol as being a Heckler&Glock AK-15 50-millimeter fully-semiautomatic assault revolver with an extended banana clip, gun-knowledgeable people will laugh so hard at me that the collective sound waves will shatter buildings.

One way to provide an in-story explanation for characters having extraordinary mental abilities is to drop in some cool-sounding neuroscience. In Carrion Comfort, Dan Simmons explains the mind-vampires’ powers by having a psychiatrist character excitedly talk about the hippocampus and EEG readings. In Firefly, River Tam's psychic abilities are created (or enhanced; we don’t get much of a clear explanation) by the surgical “stripping” of her amygdala.

Some errors can be handwaved away by appealing to the fact that we still know very little about how the brain works (Maybe some researcher in the future will discover a currently-unknown link between amygdala lesioning and psychic powers). Other errors, though, are just plain wrong.

And that brings us to today’s topic. You may have heard this one: Neuroscientists have determined that humans only use 10% of our brains. Just imagine the vast untapped potential lurking in the hidden crevices of our cerebral cortex!

This idea can be found all over the world of fiction. When I was a kid, aliens filled the unused 90% of a young boy’s brain with star charts in the Disney movie Flight of the Navigator. More recently, Jim Butcher invoked this concept in the Dresden Files novel White Night to explain how a spirit-creature was able to alter the functioning of Harry Dresden’s brain without causing permanent damage. The 2014 film Lucy was all about this trope: in that movie, Scarlett Johannson gets an accidental mega-dose of brain-growing-juice that causes her to use more than 10% of her brain, becoming smarter than Morgan Freeman, gaining phenomenal powers, and eventually becoming one with the universe (check out the trailer).

Fun stuff. There’s only one problem, though: it’s all absolute nonsense.

All of it.

Nobody’s sure exactly where this myth got started, but most historians of psychology think that it originated with a misquote of turn-of-the-century psychologist William James, who said in 1907: “Compared with what we ought to be, we are only half awake. Our fires are damped, our drafts are checked. We are making use of only a small part of our possible mental and physical resources.” Other early psychologists pointed to the fact that people can suffer brain damage but retain – or relearn – their mental capabilities, and suggested that maybe this was because the damaged areas don’t really do anything.

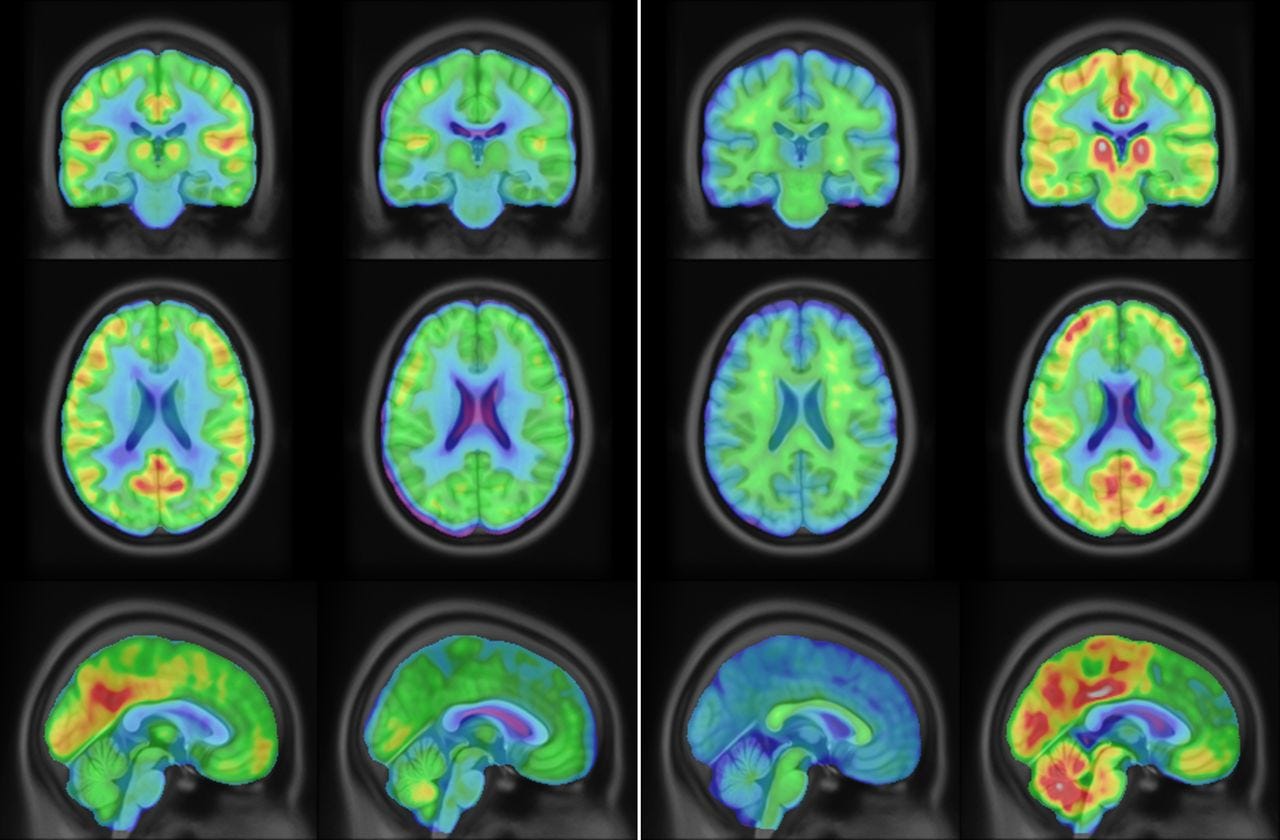

We have since learned that, in reality, we use all of our brains all of the time. This has been confirmed by neuroimaging studies; even when we are asleep, the whole brain is in a constant state of activity.

Some biopsychologists who study physiological aspects of intelligence suggest that IQ might be connected to the number of neurons in a person’s brain, processing speed, or metabolic efficiency of the neurons. So, if you want to write a story in which Professor Hypernoggin is tirelessly at work in the laboratory, developing a biological method for turning ordinary humans into super-smart brain-creatures, you do have some real options for some good technobabble in your fiction.

Just don’t say that it has anything to do with the ten-percent-of-the-brain myth.

If you liked this, click that subscribe button so that you don’t miss the next installment. If you have questions or comments about the ten-percent myth or the physiology of cognitive ability, please post in the discussion section below.

See you all next time!

I am 100% going to describe a gun as a "Heckler&Glock AK-15 50-millimeter fully-semiautomatic assault revolver with an extended banana clip" now. Because that phrase deserves to live forever.